Letters to Castolon: 1934-1940

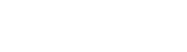

In January 2014, our discovery of an unknown cache of correspondences mailed to an “A.W. Dorgan” of Castolon, Texas sparked research that continues to rewrite the founding history of Big Bend National Park. These letters originated from some of the highest offices of state and federal government, yet virtually nothing is known about Albert W. Dorgan. Why?

On rare occasions, lack of evidence is evidence in itself. Dorgan was not simply missing from park histories, but conspicuously absent. How could there be so little mention of a man communicating directly with ranking members of Congress, the Secretaries of State and Interior, and the Secretary of the Navy?

Current histories of Big Bend portray Albert W. Dorgan as a farmer and unemployed landscape architect. Our cache of unknown letters received by Dorgan in Castolon tells a completely different tale. Yet aside from the ruins of his unique adobe home, virtually nothing documents his existence in Big Bend. The reason? He wanted it that way.

The extreme isolation of Castolon initially fueled our investigation. Was it possible that Dorgan (and his wife) lived in a town of less than 25 residents for more than a decade and avoided nearly all contact with locals? The volume of letters was equally curious. Between 1934 and 1940, Dorgan received dozens of letters from key Washington and Texas officials, national magazines, chambers of commerce, fraternal organizations, and more.

Many correspondents exhibited a notable tone of respect and deference; others reflected a sense of urgency, with several writers apologetic for delays in responding to Dorgan. Several letters referenced maps and briefs returned to Dorgan “under separate cover”—and per his request. Yet he never contacted the National Park Service or the Texas State Parks Board with his elaborate development plans. If Dorgan had any influence on park design, why did he deliberately avoid the agencies most involved in creating a park in Big Bend?

Questions emerged. Why was an alleged farmer in a remote border town receiving correspondences from the National Broadcasting Company, Warner Brothers Pictures, the National Geographic Society, and the House and Senate Committees on Military Affairs?

The history of Castolon and Dorgan was not merely forgotten, but deliberately concealed—and by the former residents themselves! During the 1960’s, interviews conducted with former Castolon residents and aviators connected to the Johnson Ranch revealed virtually no information about Dorgan. What no interviewer could know was that the residents were lying.

The alleged “commander” of the Johnson Ranch airfield—Elmo Johnson–gave several interviews but never mentioned Dorgan. In later years he refused to discuss the ranch entirely. We found it highly unusual that Dorgan avoided all contact with an airfield barely sixteen miles upriver, while submitting designs to the Secretary of the Navy for dirigibles and equipment for bomber aircraft identical to those landing at the Ranch.

In 1967, Dorgan’s longtime neighbor in Castolon claimed he was born in Germany and moved to Big Bend to start a farming partnership. In 1985, her memory improved. She recalled Dorgan’s arrival at the Johnson Ranch before moving to Castolon, and a trunk full of photos taken by Dorgan and his wife while traveling across Europe for the Department of State.

Before searching for additional background information on Dorgan, Castolon, and the Johnson Ranch, we realized there was not only something odd about Dorgan, but with the entire Big Bend park project itself.

Big Bend State Park: Peculiar Origins?

After reading accounts of the founding of Big Bend National Park, many historical “facts” appeared highly suspect. In our search for answers, we finally realized that we were looking for answers to questions no one ever asked. Here are a few questions worth considering.

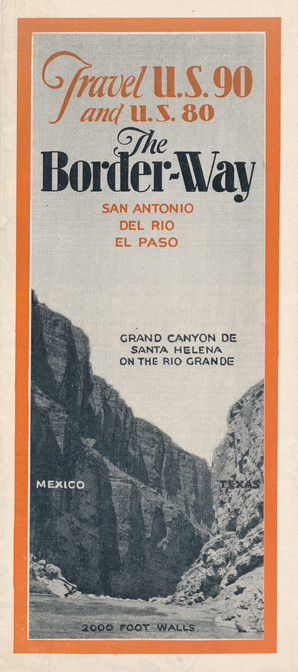

An ideal location for a weekend getaway? In March 1933, as Texans struggled for survival in the Great Depression, Austin legislators decided that the Big Bend region was the perfect location to establish a state park. Visitors were welcome to traverse over 115 miles of unimproved roads from the nearest town, only to arrive at a scenic outlook with no facilities for visitors. Park guests were welcome to drink from the Rio Grande, as water was not tapped in the Chisos Mountains until April 1934—nearly a year after the state park was proposed.

An unusual group of conservationists? The founding fathers of Big Bend shared more than a love of conservation. Common threads? Water and the War Department. State legislator Robert Wagstaff of Abilene first proposed a state park in Big Bend, but also served in WWI and supported key water development projects across Texas. Rep. R.Ewing Thomason wrote and introduced the enabling legislation for Big Bend, but also worked on the TVA hydroelectric dam project and served as Vice-Chairman of the House Committee on Military Affairs. Senator Morris Sheppard introduced a bill in the Senate to create a federal park in Big Bend, but also served as Chairman of the Senate Committee on Military Affairs and supported hydroelectric projects.

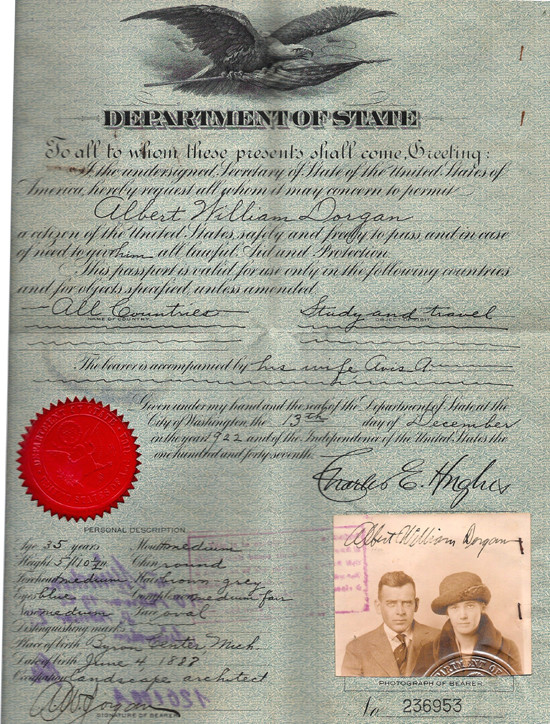

A CCC camp building a road to nowhere?

The combined influence of Senator Sheppard and Congressman Thomason allowed Texas to establish not one, but two CCC camps in Big Bend. In 1934, the CCC began construction of a seven mile road leading into the Chisos Basin–with no input from the National Park Service. A half Hispanic work force created a language barrier among enrollees, and the original camp included only two staff members and no educational advisor. The extreme isolation of the camp increased wear on vehicles, increased fuel consumption and added considerable expense for construction materials due to distance traveled. Cost for food and camp supplies was likewise excessive. Overall, the CCC camps in Big Bend were massive investments in a park virtually inaccessible to the public.

Albert W. Dorgan: Master Planner of Big Bend

With no useful information on Dorgan available from any source, there was only one place left to search—the National Archives. Fortunately, Dorgan’s correspondences from the Department of State contained the central file code that led us to solve the greatest untold mystery in National Park Service history.

Despite the growing mountain of hard evidence supporting our claims about Dorgan and the Big Bend mystery, skeptics remain. Perhaps the best question to ask is simply what knowledge, skills, and abilities would a person need to produce the maps, plans, and written material created by Dorgan? One can debate whether Dorgan’s ideas were viable or realistic, but creating this material required the skills of a master planner with access to military data unavailable to the public.

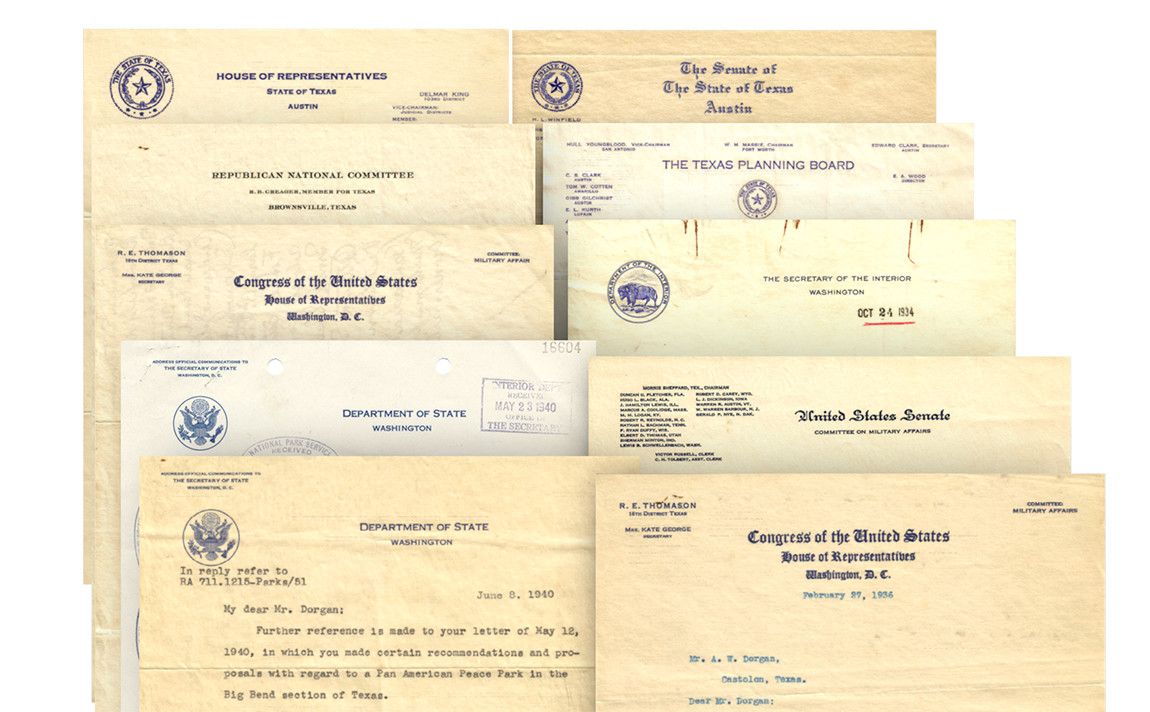

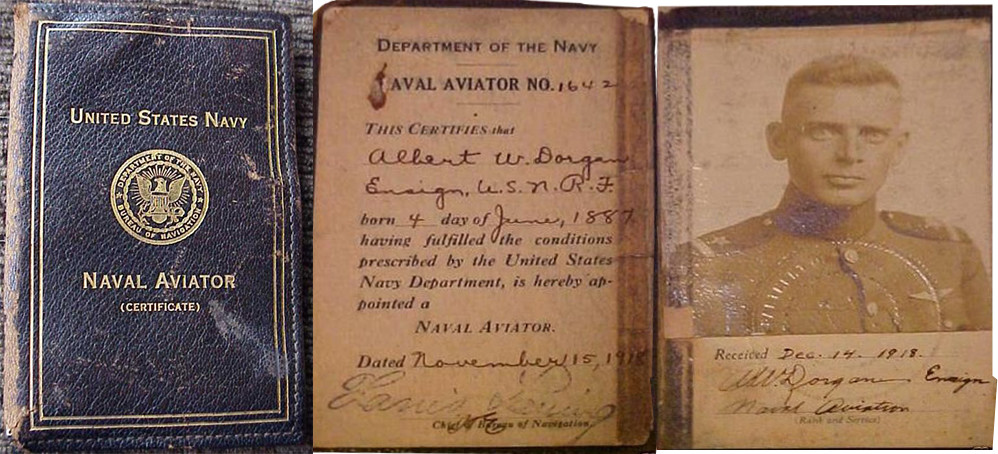

Drafting a “suggested development plan” for Big Bend required formal training in drafting, cartography, hydrology, horticulture, landscape architecture, and residential construction. Dorgan mastered all these skills before his 1929 arrival in Big Bend. In 1914, he received a degree in horticulture from the Michigan Agricultural College and began developing homes in Toledo, Ohio before enlisting in the Navy. In March 1918, Dorgan began training at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology before completing flight school in Miami and Pensacola, Florida. He completed advanced training in the new fields of aerial photography and observation before receiving his pilot certificate and rank of Ensign in the United States Naval Reserve Force (USNRF).

Dorgan studied hydrography as a member of the Bureau of Navigation, and was no stranger to massive public works and waterways. In 1919, Dorgan served at the strategic Coco Solo Naval Air Station in the (former) Panama Canal Zone and observed the Panama Canal firsthand. His work with the USNRF also put him in contact with the Office of Naval Intelligence. Dorgan left the service in 1919 but did not abandon his navy connections.

The Dorgan Plan: Development or Destruction?

The potential construction of dams and roads in Big Bend was not a secret. Dorgan shared his April 1934 development blueprint with the Alpine Chamber of Commerce, so what did local residents think of the overall idea of a massive recreation area in Big Bend? Was flooding canyons to create reservoirs an act of preservation or destruction?

Perhaps the most qualified Texan to answer this question is Everett E. Townsend, cosponsor of the original bill to create a state park in Big Bend and credited today as the “father of Big Bend National Park.” In a letter dated 25 November 1933, Townsend explained to Colonel Robert H. Lewis, Ground Control Squadron at Fort Sam Houston, that dam construction and rescuing Big Bend were mutual pursuits.

Townsend suggested that “If a man would erect a dam two hundred and fifty feet high and about five hundred long, it would create a reservoir sixty miles long and fifteen or twenty wide. The power generated by such a dam could electrify all of West Texas and the Southern Pacific from San Antonio to El Paso.” Townsend closed his letter to Col. Lewis with his dream that Big Bend “could forever stay, like it was more than forty years ago as I first saw it, but that day has already passed; it is gone, and the only way we can rescue and preserve it is to take it over and restore it for the use of those who are to come after us.”

In 1933, Townsend circulated a four page letter by Col. Lewis. With phrases and a writing style eerily similar to known writings by Dorgan, Lewis shared his vision of Big Bend development with Townsend::

“A dam 250 to 300 feet high in either one of the three canyons would create a reservoir covering more than one hundred square miles, dotted with islands, bays and straits wedging themselves back among the mountains. The control given over the river by such a dam would enable the regulation of its flow, ensuring a more equal and seasonal distribution of the waters in the rich valleys of its lower reaches and largely minimize the danger of excessive floods, so prevalent in those regions. The enormous possibility of power that could be developed by the proposed project can be figured only by competent engineers.” Col. Robert H. Lewis, Ground Control Squadron, Fort Sam Houston to Townsend, 1933.